It was July 24th and for Willie Novotny age 7, school was out for the summer. On that cool and damp Saturday morning, Willie woke up well before dawn, much too excited to sleep. His nine year old sister Mamie, (sometimes called Minnie) woke up soon after. Willie quickly dressed in his Sunday-best clothes and came to the breakfast table. Their mother Agnes, age 35, likely prepared a traditional Czech breakfast of dumplings and eggs, dark rye bread, maybe a rohlík yeast roll with butter and jelly or maybe on a good day, a slice of salami or cheese. Their father, James (Vaclav), born Ponedraz Bohemia, also age 35 was the last to the table for his morning hot cup of coffee. He looked forward to spending a rare and wonderful day with his family.

It was July 24th and for Willie Novotny age 7, school was out for the summer. On that cool and damp Saturday morning, Willie woke up well before dawn, much too excited to sleep. His nine year old sister Mamie, (sometimes called Minnie) woke up soon after. Willie quickly dressed in his Sunday-best clothes and came to the breakfast table. Their mother Agnes, age 35, likely prepared a traditional Czech breakfast of dumplings and eggs, dark rye bread, maybe a rohlík yeast roll with butter and jelly or maybe on a good day, a slice of salami or cheese. Their father, James (Vaclav), born Ponedraz Bohemia, also age 35 was the last to the table for his morning hot cup of coffee. He looked forward to spending a rare and wonderful day with his family.

About 6:00 am, the family of four would likely have left their house at 5527 West 24th Place in a blue-collar working class neighborhood of Czech’s and Polish. About 10 minutes later, and less than a half mile walk, they would have entered the Metropolitan West Side Elevated, 56th Avenue Station at about 2126 S. 56th Avenue (now Central Avenue).

About 6:00 am, the family of four would likely have left their house at 5527 West 24th Place in a blue-collar working class neighborhood of Czech’s and Polish. About 10 minutes later, and less than a half mile walk, they would have entered the Metropolitan West Side Elevated, 56th Avenue Station at about 2126 S. 56th Avenue (now Central Avenue).

They never returned home.

It was a small neighborhood “L” stop, opened just three years earlier, at the time, the western terminal of the Douglas Park Branch. It was not really elevated there, but rather at grade level. They entered the small, wood-frame station house with clapboard siding, through a set of double doors . The station was set between the tracks where they paid their fare at a small ticket booth near the entrance . The interior was floor-to-ceiling tongue-in-groove paneling with wood floors and paneled ceilings. There were incandescent lights for illumination. and a boiler stove for heat. The rear opened out onto an island platform where they boarded the next eastbound “L” car for the 25 minute ride to downtown Chicago, probably Willie’s first.

It was a small neighborhood “L” stop, opened just three years earlier, at the time, the western terminal of the Douglas Park Branch. It was not really elevated there, but rather at grade level. They entered the small, wood-frame station house with clapboard siding, through a set of double doors . The station was set between the tracks where they paid their fare at a small ticket booth near the entrance . The interior was floor-to-ceiling tongue-in-groove paneling with wood floors and paneled ceilings. There were incandescent lights for illumination. and a boiler stove for heat. The rear opened out onto an island platform where they boarded the next eastbound “L” car for the 25 minute ride to downtown Chicago, probably Willie’s first.  The Novotny family looked forward to an exciting steamship trip and then a happy picnic in Michigan City, Indiana.

The Novotny family looked forward to an exciting steamship trip and then a happy picnic in Michigan City, Indiana.

James and Agnes Novotny, were both Czech Republic immigrants born 1879. Both were 24 when they married on April 17 1904. Mamie was born February 5 1906 and Willie was born on May 23 1908.

James and Agnes Novotny, were both Czech Republic immigrants born 1879. Both were 24 when they married on April 17 1904. Mamie was born February 5 1906 and Willie was born on May 23 1908.

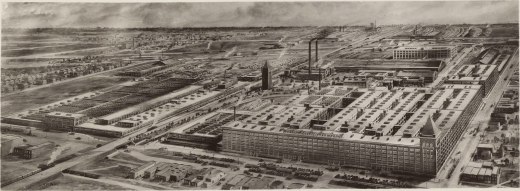

James was a hard working man, employed at a huge 5-million-square-foot factory on 22nd Avenue (later renamed Cermak Road years later). He had been working there for several years, often six days a week, earning something like $13 per week. James was a skilled cabinetmaker in the woodworking department of the Western Electric Hawthorne Works. He and his fellow cabinetmakers built and repaired items like switchboard cabinets, phone booths and magneto wall phones popular at the time.

The plant was named for Hawthorne, Illinois, the small town that later became Cicero Illinois. The mega complex, opened in 1905 was the manufacturing arm of the Bell System where, at the time, more than 25,000 people designed, assembled and tested some 90 percent of the nation’s telephones, switchboards and telegraph equipment. In addition, Western Electric assembled typewriters, sewing machines, electric fans, vacuum cleaners, microphones, vacuum tubes, radios, motion picture sound systems, and more. Hawthorne Works consisted of many buildings and even had its own private railroad, the Manufacturers Junction Railroad, with more than 10 miles of track.

So on July 24, 1915, at about 6:30 am, James, Agnes, Mamie and Willie arrived at the Clark/Lake elevated stop, walked down the stairs and north to South Water. There was the large steamship dock on the south bank of the Chicago River between Clark and LaSalle Streets. Willie was beside himself with boyish excitement. James had purchased four tickets for the round trip excursion to Michigan City.  A ticket for he and his wife Agnes were $1.00 each, Tickets for Willie and Mamie were 35 cents each.

A ticket for he and his wife Agnes were $1.00 each, Tickets for Willie and Mamie were 35 cents each.

At about 6:50, along with thousands others, they boarded the SS Eastland, built 1903, more recently owned by the Michigan Transportation Company.

It was a twelve year old passenger ship, 279 feet long and four decks tall, engaged in the lucrative excursion business and based in Chicago. Its itinerary usually consisted of four hour trips to South Haven, Michigan. She was nicknamed the “Speed Queen of the Great Lakes”, but had a checkered past.

The Eastland was one of four other Great Lakes passenger steamers, the Theodore Roosevelt, Petoskey, Racine, and Rochester, chartered this day to take thousands of Western Electric’s employees and families to Michigan City’s Washington Park for a company picnic., a major event in the lives of the workers, many of whom could rarely afford to take holidays.

The Eastland was one of four other Great Lakes passenger steamers, the Theodore Roosevelt, Petoskey, Racine, and Rochester, chartered this day to take thousands of Western Electric’s employees and families to Michigan City’s Washington Park for a company picnic., a major event in the lives of the workers, many of whom could rarely afford to take holidays.

By 7:10 am, the ship was packed with 2,572 passengers many standing on the open upper decks. It then began to list slightly to the port side away from the wharf. At 7:28 am, the Eastland lurched sharply in perfectly calm water, in excellent weather, other than a misty rain, with no explosion or fire.

It rolled completely onto its port side, coming to rest on the river bottom. Hundreds of people were trapped inside by the water and the sudden rollover; some were crushed by heavy furniture. Although the ship was only feet from the wharf, a total of 844 passengers and four crew members died including the entire Novotny family. It was the largest loss of life from a single shipwreck on the Great Lakes. There were many theories presented as to the cause, but no firm conclusions were ever proven.

The bodies of the Novotny family were taken to a temporary morgue and then to an undertaker, one of dozens need to tend to the dead. Sadly, little Willie was the very last victim to be identified, and for several days was known only as a cold “Victim #396”. Days later, two school chums identified his body in the Sheldon Undertaking Rooms at 912 West Madison.

The funeral for all four members of the Novotny family was held together on July 31, 1915. It was provided by the Bohemian Relief Society at the Skola Vojta Naprstek Bohemian School at 26th and Homan Avenue. It was a huge funeral attended by Chicago’s Mayor Thompson and over 15,000 Chicagoans. It was attended by many hundreds of school children and 200 boy scouts. There were 450 of Willie’s schoolmates, 150 more from his neighborhood, and still hundreds more from surrounding neighborhoods.

Willie and his family were then taken to Bohemian National Cemetery on north Pulaski Avenue by a one and a half mile long procession. Buildings along the way were draped in black and white crepe. 15,000 mourners overflowed a second funeral service in the cemetery chapel. There was an unusual, second open casket viewing.

Willie and his family were then taken to Bohemian National Cemetery on north Pulaski Avenue by a one and a half mile long procession. Buildings along the way were draped in black and white crepe. 15,000 mourners overflowed a second funeral service in the cemetery chapel. There was an unusual, second open casket viewing.

One of the few surviving family members attending was Mrs. Frances Martinek, Willie’s heartbroken maternal Grandmother.

And all of Chicago cried

My grandparents both worked for Western Electric at the time. They were due to go on board the Eastland, but found the long line daunting. They decided to do something else downtown. I’m glad they did!

LikeLike

Simply another great story. A happy one at that! Thanks!

LikeLike

I lost several 2nd and 3rd cousins on this fateful day. All were in their teens. It was so very sad. Anna Pesch

LikeLike

I am so sorry! Thank you for writing

LikeLike

MY GRANDMOTHER YOUNGER SISTER WAS ON THAT SHIP AND LOS HER LIFE. REST IN PEACE ALL THAT WERE LOST.

LikeLike

So sorry to all that lost their loved ones. It’s heartbreaking, especially when it was suppose to be a joyous and fun excursion.

LikeLike

My 12 year old Grandmother was in line with her mother, her aunt and her cousin. Her Aunt suddenly became sick to her stomach, so they got of line and went home. She told us that entire departments at Western Electric were wiped out by the capsizing of the Eastland. She couldn’t talk about the Eastland tragedy with crying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great story! I hope you don’t mind that i am gonna use this for a document for school

LikeLike