Back in the day, if you were a farmer bringing your goods into the city to sell , your horse and wagon would often sink deep into muddy rutted roads. This was especially true during the spring snow melt and torrential summer rains.

The solution were Plank roads radiating out of the city often called “the farmers railroad”. They were a very important part of Chicago’s transportation for a few years, with 50 miles were built between 1848-1855 at a cost of approximately $150,000. Although they were a huge improvement over mud and ruts, Plank roads were so rough that they were often called “corduroy roads”.

Plank roads were cheap to build, usually heavy planks a few inches thick and eight feet long attached crosswise to wooden stringers set into the roadbed.. Pine and hemlock were sometimes used for planking, but oak and black walnut, although more expensive, were more durable and long-lasting.

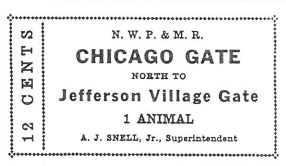

Plank Road companies recouped their investments by collecting tolls at toll gates at regular intervals infuriating farmers who needed to bring their products to market without added costs. As one example, Amos J Snell made a ton of money charging farmers on the Elston and Northwest (Milwaukee Avenue) plank roads. More about him later. Some farmers were really good at finding ways to bypass the toll roads, hence streets named Dodge. Other farmers simply burned down the toll house.

Plank roads only lasted one or two years. Planks soon warped, decayed, and frequently floated away. Some were stolen or were simply “borrowed” by neighboring settlers. Rotting planks, due to ground moisture and the weather gave way under the weight of horses and wagons, damaging loads injuring the farmer and animals alike. After a few years, with little or no maintenance, most plank roads became so uncomfortable and dangerous that they were abandoned. The depression of 1857 and the spread of rail networks were the final blow for the plank Road companies replaced by gravel, brick roads, and streetcars.

Southwest Plank Road

One of the first plank roads followed what today we know as Ogden Avenue bridging what was called the “nine-mile swamp”. It opened in September 1848 for distance of about 9 or 10 miles to Doty’s Tavern in Lyons, at what is now the intersection of Ogden Ave with Joliet Ave. In 1850 it was extended to Brush Hill and Fullersburg (now Hinsdale), and In 1851 was extended again via the Naperville and Oswego plank road for a total of 22 miles .

The predecessor of the Southwest plank Rd. was the Barry Point road the first highway out of Chicago on which any attempt at road building was ever made, and became the approximate route of the the Southwest plank road. It left Chicago on modern Madison Street to Western Avenue where it became known as the Barry Point Trail and then southwest to Laughton’s Tavern.

Southern plank road

the Southern plank Road was organized February 12, 1851 constructed by way of State Street and Vincennes Avenue as far as Kyle’s (Kile’s) Tavern, some ten miles out, for about $21,000

Blue Island Plank Road

Built 1854, it was one of two last additions to the plank road system built in Chicago, it was 13 miles in length running on Blue Island Avenue south to the city’s southwest border at about today’s Archer and Western Avenue

Now turning to Chicago’s north side

Whiskey Point Road

It was originally a muddy Indian trail called army trail road during the Blackhawk war , then Whiskey Point Road in 1854 – now Grand avenue beginning at at about Armitage.

n 1862 Michael Moran who declared that Chicago was a “grand place to live.”established a hotel at Whiskey Point, but the area remained rural for some 20 years.

Lake Shore Plank Road

Also known as Chicago, Rosehill, and Evanston plank Road , and the “Rosehill and Evanston” road . It was 5 miles in length built by the Lakeshore Plank Road Company about 1854 to make an easier trip to Lakeview House built on the lake shore in 1853 by James H. Rees and E. E. Hundley. Lake Shore Plank Road was the last wooden plank road built in Chicago.

It ran from Graceland Avenue (Irving Park) north through Rogers Park, along what is now Clark Street. It paralleled Lake Michigan from North Ave. and Clark St. to Green Bay Road, to Hood’s Tavern on the Green Bay Trail. It was considered quite a Boulevard, a “fashionable driveway” in the day

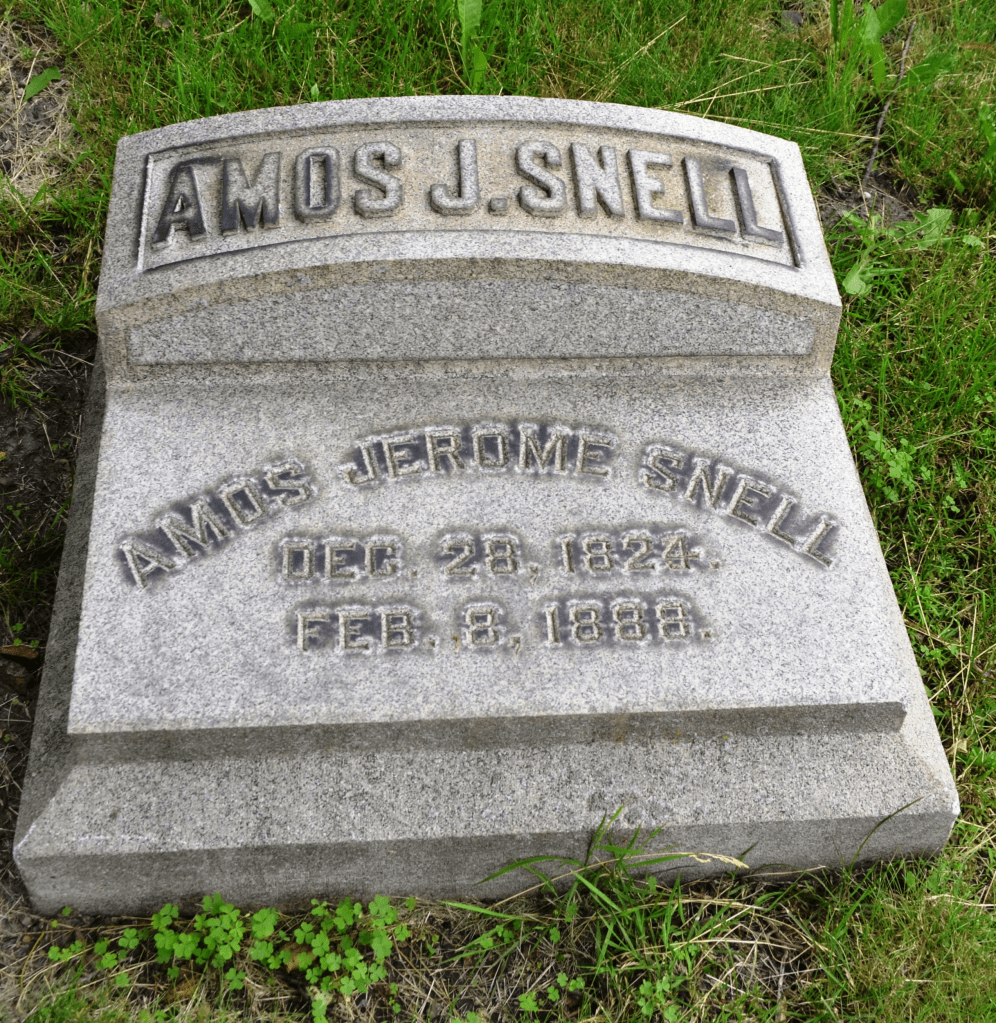

Meet Amos Snell – toll road baron

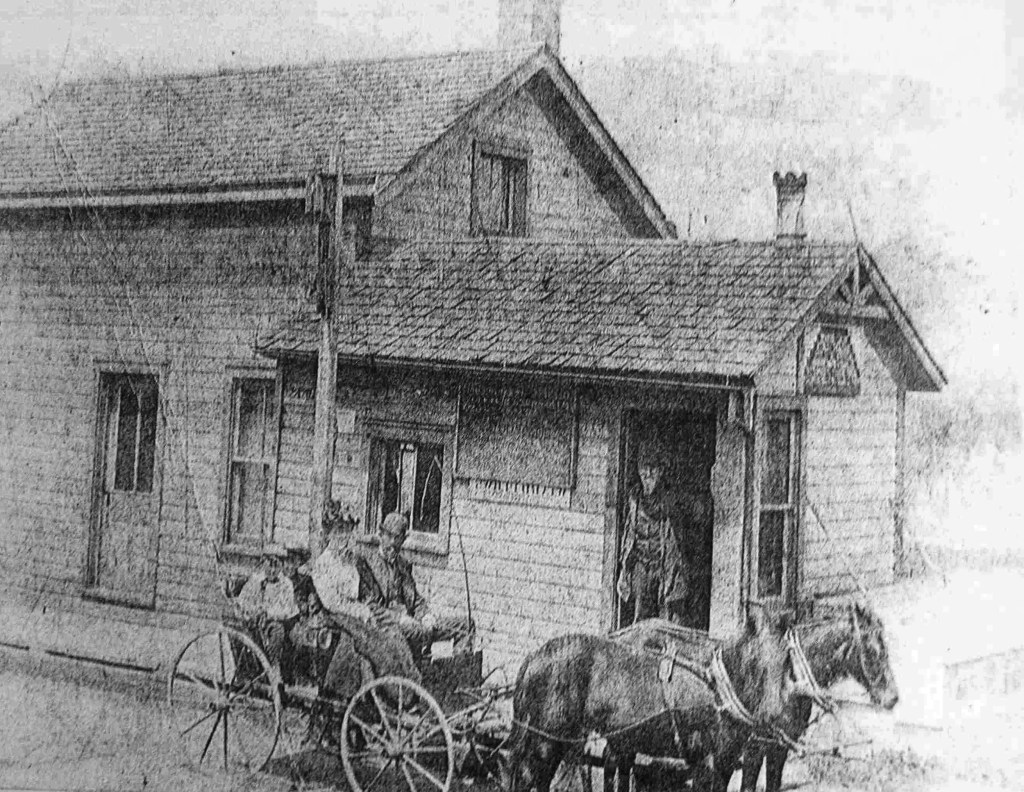

He was born in Little Falls New York 1804 and arrived in Chicago in 1837 with his bride , horse and wagon, and only $22. In his early years in Illinois he had a roadside Inn in Schaumburg and became proprietor of a hotel and a grocery in Jefferson.

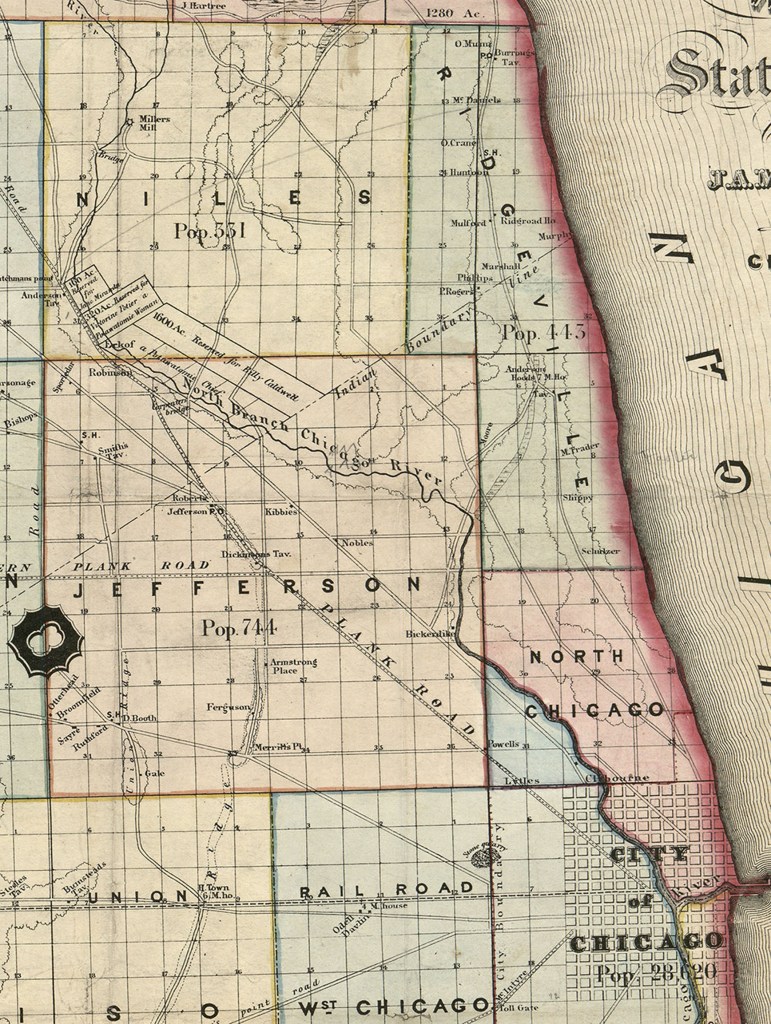

Snell bought from Cook County the right-of-way which extended from Chicago’s city limits to what was then the village of Jefferson, giving Snell a monopoly on all the major roads that led into Chicago.

Snell gave northwestern farmers and merchants no choice but to pay whatever he wanted if they wanted to market their goods. For years money literally rolled in what with the many Polish and bohemian picnics held outside the city limits, the many funerals, and the truck farmers coming to city markets. He had supposedly been charging the outrageous fee of 2-1/2 cents per mile to travel from the center of the city along the 10 or so miles to the northwest. His tolls at one point provided him with nearly $800 a day with fees collected at several toll gates.

His tolls were incredibly disliked

A group of men dressed as wild Indians set fire to the Toll house one night in the spring of 1889. The plot to burn down that Toll house was hatched in a saloon at Milwaukee and California. Farmers would stop in the saloon and over several steins of beer grew unhappy about being separated from their hard-earned money at Snell’s gates only a few yards away at Milwaukee and Fullerton.

The toll road was only one of his enterprises. At the time of his death Amos was reputed to be Chicago was wealthiest property owner’s fortune was estimated at more than $3 million. Besides the real estate he owned in the city, he possessed large tracts in Jefferson, Park Ridge, Schaumburg and in the State of Iowa.

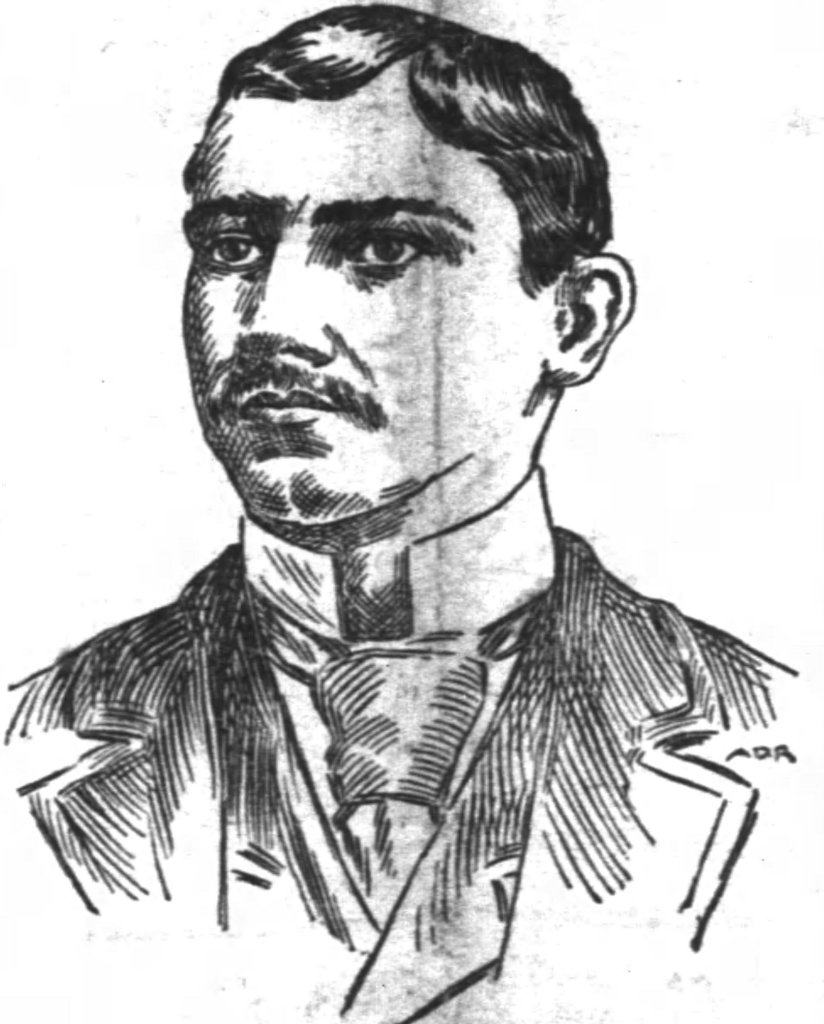

Amos J. Snell, the millionaire real estate owner and acknowledged wealthiest land proprietor on the West Side, was shot dead in the hallway of his brown-stone residence, 1326 West Washington Blvd., at the northwest corner of Ada street and Washington boulevard, Wednesday morning at about 2 o’clock. The murder was described as one of the largest individual owners of real estate in the city and the “most sensational ever committed in Chicago,”

Police arrested William B. Tascott on his deathbed at the Cape Nome Gold Diggings in Alaska in 1889. But 21 years later, James Gillan, labeled a “professional crook” confessed on his deathbed that he, not Tascott, had killed Snell while burglarizing his home.

After Snell’s death, the city of Chicago, which had extended its boundaries into areas containing parts of the road, began to tear down the toll gates because toll roads were not permissible in the city.

Snell died from shock and hemorrhage caused by pistol shot wounds. Over 2,000 people were reported to have attended the funeral held within the library at his residence. After the funeral over 100 carriages proceeded to Rose Hill Cemetery for the burial. Mr. Snell left a wife Henrietta, two daughters and a son. His children were all married at the time.Snell did not leave a will, and his heirs moved to secure his estate, particularly some 400 real estate properties and the valuable toll roads.

The next three listings below, the Northwestern plank Road, the Elston plank Road, in the Western plank extension were all owned by Amos Snell

Northwestern Plank Road

also known as “Snell’s Road”, Originally designated as the “ lower trail” a travel route originally established by Native Americans,

The plank road was originally built by the Northwestern Plank-Road Company under an 1849 grant by the state of Illinois. In September 1849 planks were laid 8 miles from the Galena Depot along Milwaukee Avenue as far as Oak Ridge which is now Irving Park Road. 8 miles out. In the next two years the mainline was extended 3 miles beyond Dutchman point (now Niles) toward Wheeling, a total of about 18 miles.

In 1870, Amos Snell purchased the Northwestern Plank-Road toll road. improved it with gravel but also erected more toll gates, it became a notorious toll road much to the public’s anger.

.

The Western Plank Road

From the Northwestern Road at Oak Ridge (Irving Park Road in Jefferson) , the Western Plank Road ran west to the boundary of Du Page County, where it connected with the Elgin and Genoa Plank Road, which ran through Elgin to Genoa in Kendall County, fifty miles from Chicago.

The Elston plank Road

also known as the Snell toll road – originally an Indian trail designated the “upper trail”. Elston Avenue in the early days was originally known as Elston Road .

It was named after Daniel Elston,(1780-1855) a London merchant who immigrated to Chicago in the early 1800s established several businesses, making soap, candles, bricks, beer and whiskey; he also served as a school inspector and an alderman, and founded a bank. Elston is buried in Graceland Cemetery

There were three toll houses on N. Elston alone: its southern entry point at W. Division Street (near Goose Island), one just south of Lawrence Avenue at Elston, and another farther north where it merged with N. Milwaukee.

Describe by Andreas “as a crooked wagon track leading from Kinzie Street through Jefferson to the Western part of Niles and thence on through Northfield toward Deerfield it runs parallel for about 9 miles with Milwaukee with the two merge “

William Ringler one of the old toll gate keepers in an interview once said:

“I was on the job for 14 years and I guess I took in more money than any other gatekeeper. One Sunday Polish and Bohemian picnics at Niles in Des Plaines, and the new cemeteries then opening up my receipts were $790. The average from all gates at that time was about $100 a day.”

Both Elston plank Road and the Northwest plank Road on Milwaukee continued to operate until 1889 when the Township of Jefferson was annexed the city of Chicago. Indignation of farmers staged a modern version of the Boston tea party and organized bands of fake Indians that swept down upon both plank roads chop down the toll gates and build great bonfires there with as a token of their Declaration of Independence further paying a toll for the right to travel on these great highways.

If you have enjoyed this story about plank roads and Amos Snell, please leave a comment below.

I cordially invite you to subscribe to Chicagoandcookcountycemerteries so that you will receive notification of the many upcoming stories about Chicago and it’s cemeteries. Subscribing is always free.

You can also contact me anytime at bartonius84@Hotmail.com

Thanks, Barry A. Fleig

And while you’re at it, check out this related story of the cemetery once along the Western Plank Road in Jefferson (now Irving Park Road)